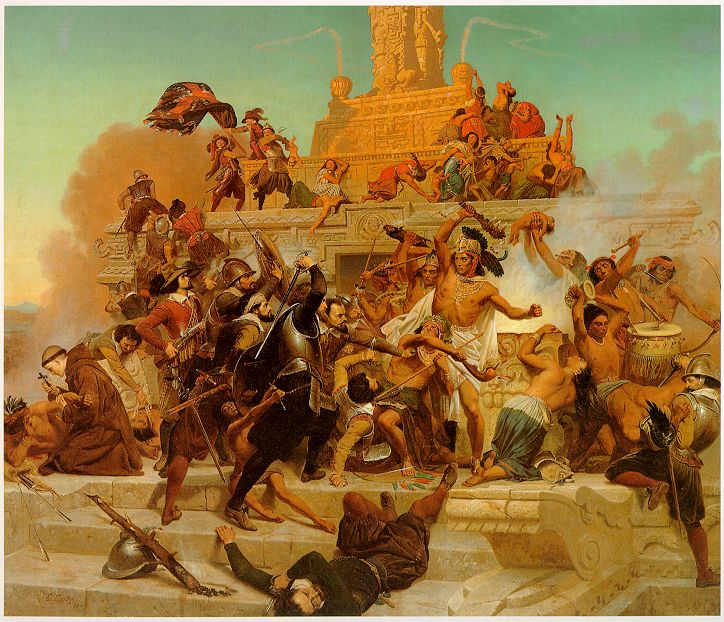

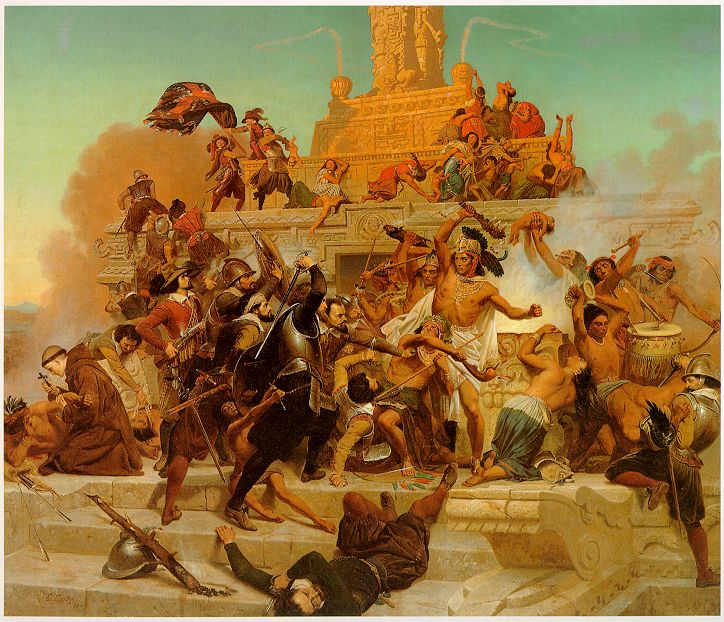

"The Storming of the Teocalli." (1848). Emmanuel Leutze.

"The Storming of the Teocalli." (1848). Emmanuel

Leutze. (Cortez with stout armored band fights his

way back into Tenochtitlan, June, 1520. Based on

Prescott's description)

The situation as reconstructed by modern historians is not as melodramatic as the summary and

description appearing in the passages from Prescott below. Cortez, having exited Tenochtitlan

with most of his force to deal with Spanish forces from Cuba hostile to his enterprise,

overcame and absorbed them. The combined force then re-entered the Mexica city on June 24

without opposition, to rejoin the beleagured Alvarado and his men, only then to find

themselves pent up and in effect besieged within the now hostile city which had turned against

Cortez and the captive Moctezuma.

The Spanish began house clearing operations around the perimeter of the buildings to which they

were confined in preparation for an eventual fighting retreat. The "Storming of the Teocalli"

reflects a Spanish assault on the nearby pyramid temple of Yopico, a hard fought battle up

the vertiginous steps. Reaching the top of the pyramid (teocalli) the Spanish cast down the

"idols," images of the Mexica gods, burned those they could not overturn, and thrust and

tumbled the Mexica priests after them. It is probabled that among the cast down objects in

this sortie was the famous Aztec Sun Stone, probably the best known symbol of

Mexican culture. Contrary to Prescott's envisioning, therefore, this battle, though

stenuous, was not a prodigious fighting re-entry into Tenochtitlan and, more importantly,

was not fought atop the great teocalli of the Plaza Mayor, the pyramid dedicated to the

twin gods, Tlaloc the god of Rain and Huitzilopochtli, the patron War God of the Mexica.

Prescott loads his narrative with a symbolism that is close to allegory - the

Christian Spaniards fighting to topple the pagan Gods of the Barbarian Mexica and replace them

with Christian images at the very heart and pinnacle of the Aztec domain.

reference, Hugh Thomas, Conquest: Montezuma, Cortes, and the Fall of Old Mexico, New York:

Simon and Schuster, 1993, pp. 402-403.

(reference, William H. Prescott, HISTORY OF THE

CONQUEST OF MEXICO, 2 vols., Philadelphia: J.B.

Lippincott Company, 1892, II, 63-67)

EMANUEL LEUTZE, THE STORMING OF THE TEOCALLI, 1848--BASED ON

WILLIAM PRESCOTT'S DESCRIPTION IN HIS 1843 *HISTORY OF THE

CONQUEST OF MEXICO.*

(reference, William H. Prescott, HISTORY OF THE CONQUEST OF

MEXICO, 2 vols., Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1892,

II, 63-67)

THE FIGHT ATOP THE TEOCALLI (Temple):

BACKGROUND: CORTEZ HAD LEFT A SMALL GARRISON OF SPANISH TROOPS

IN TENOCHTITLAN TO GUARD MOCTEZUMA AND HIS TREASURE WHILE HE

DEALT WITH A HOSTILE SPANISH FORCE THAT HAD LANDED FROM CUBA.

THIS GARRISON, UNDER THE COMMAND OF ALVARADO, HAD FALLEN UPON

RELIGIOUS CELEBRANTS DANCING IN HONOR OF THE RAIN GOD, TLALOC,

AND HAD MASSACRED THEM [SEE IMAGE 0017]. AT THIS POINT THE

AZTECS ROSE UP AGAINST THE SPANISH. CORTEZ IN THE MEANTIME HAD

TAKEN THE CUBAN FORCES BY SURPRISE AND WON THEM OVER TO HIS

CAUSE. HE THEN HAD TO FIGHT HIS WAY BACK INTO A HOSTILE CITY TO

SUCCOR ALVARADO AND REGAIN ACCESS TO MOCTEZUMA AND THE MEXICAN

TREASURE. THE DATE IS NOW JUNE 24, 1520.

THE CLIMACTIC STAGE OF THIS BATTLE WAS A THREE HOUR STRUGGLE BETWEEN THE SPANISH AND THE AZTECS ATOP THE GREAT TEOCALLI DEDICATED TO HUITZILOPOCHTLI [wee-tsee-loh-POHTCH-tlee], THE WAR GOD, THE HUMMING BIRD OF THE LEFT, THE PATRON GOD OF THE MEXICA. THE SPANISH STORMED THE PYRAMID AND, ON "THIS AERIAL BATTLEFIELD, ENGAGED IN MORTAL COMBAT IN PRESENCE OF THE WHOLE CITY," TO QUOTE PRESCOTT. ON THE FIELD ATOP THE PYRAMID, AGAIN TO QUOTE PRESCOTT, "NO IMPEDIMENT OCCURRED. . EXCEPT THE HUGE SACRIFICAL BLOCK, AND THE TEMPLES OF STONE WHICH ROSE TO THE HEIGHT OF 40 FEET . . . ONE OF THESE HAD BEEN CONSECRATED TO THE CROSS. THE OTHER WAS STILL OCCUPIED BY THE MEXICAN WAR-GOD. THE CHRISTIAN AND THE AZTEC CONTENDED FOR THEIR RELIGIONS UNDER THE VERY SHADOW OF THEIR RESPECTIVE SHRINES; WHILE THE INDIAN PRIESTS, RUNNING TO AND FRO, WITH THEIR HAIR WILDLY STREAMING OVER THEIR SABLE MANTLES, SEEMED HOVERING IN MID AIR, LIKE SO MANY DEMONS OF DARKNESS URGING ON THE WORK OF SLAUGHTER!"

The following is a close paraphrase from William Truettner, "Prelude to Expansion: Repainting the Past," in THE WEST AS AMERICA: REINTERPRETING IMAGES OF THE FRONTIER, Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. 59-62

EMANUEL LEUTZE'S PAINTING OF THIS BATTLE WAS INSPIRED BY THIS DESCRIPTION AND LIKE PRESCOTT'S WORDS TILTS TOWARD THE SPANISH.

THE TEMPLE OF THE WAR-GOD AT THE TOP IS A SQUAT UGLY MENACING STRUCTURE, A PRIMITIVE BARRICADE AGAINST LIGHT AND REASON. THE TOWER, WITH ITS CRUELLY DISTORTED HUMAN FACES IS BATHED IN A DIABOLICAL RED LIGHT. ALTHOUGH RESISTANCE IS FIERCE THE FLOW OF ENERGY AND VICTORY IS WITH THE SPANISH--THE AZTECS ARE POISED IN RECOIL. THE ADVANCING SPANIARDS, CLAD IN BLACK ARMOR, RESEMBLE HUMAN DREADNOUGHTS--THERE IS NO DOUBT THAT THE MOMENTUM OF TECHNOLOGY AND CIVILIZATION IS IN THEIR FAVOR. [IN A SIMILAR FASHION, THE US ARMY, EQUIPPED WITH THE LATEST IN RIFLES AND WEAPONRY, HAD PREVAILED OVER THE MEXICAN ARMIES IN THE LATE WAR.] THE AZTECS BATTLE HALF NUDE, WEARING JEWELS, BRIGHT CLOTHES, FANCIFUL HELMETS SUGGESTIVE OF THEIR DECADENCE. TO THE RIGHT, ABOVE THE DRUMMERS, ONE OF THEIR PRIESTS HOLDS ALOFT A PARTLY DISEMBOWELLED INFANT OFFERED IN SACRIFICE. [INFANT SACRIFICE WAS NOT PART OF THE AZTEC RITUAL WHICH EMPHASIZED THE OFFERING OF WARRIOR OPPONENTS TAKEN IN BATTLE] AT THE FAR LEFT A SPANISH PRIEST OFFERS LAST RITES TO A DYING MEXICAN --AT LEAST ONE SAVAGE SOUL WILL BE SPARED FROM HELL. JUST BEHIND THE PRIEST A SPANISH SOLDIER PLUCKS A NECKLACE FROM AN AZTEC CORPSE--WE ALL KNOW HOW GREEDY THOSE CONQUISTODORES WERE APPLAUDED IN ITS DAYS BY THE CRITICS AND PUBLIC, LIKE ALL PAINTINGS, LEUTZE'S WORK DOES DOUBLE, EVEN TRIPLE DUTY. IT COMMENTS NOT ONLY ON PRESCOTT'S HISTORY, BUT ON THE JUST ENDED MEXICAN-AMERICAN WAR--GENERAL WINFIELD SCOTT HAD FOLLOWED LITERALLY IN CORTEZ'S FOOTSTEPS AND THE VICTORIOUS US WAS SEEN AS BRINGING TO THE BENIGHTED MEXICANS THE FRUITS OF A SUPERIOR CIVILIZATION AND RELIGION. AND ONE CAN ALMOST READ INTO THE PAINTING A COMMENTARY ON THE INDIAN-WHITE ENCOUNTERS OF THE 19TH CENTURY--WHERE SOME OF THE WORST WARS WERE YET TO COME. THE STORMING OF THE TEOCALLI THEREFORE REPRESENTS THE FUTURE AS WELL AS THE PAST.

IN PRESCOTT'S WORDS, THE SUBJECT REPRESENTED: "THE FINAL STRUGGLE OF THE TWO RACES--THE DECISIVE DEATH GRAPPLE OF THE SAVAGE AND THE CIVILIZED MAN. . . WITH ALL ITS IMMENSE RESULTS."

Truettner notes (see above reference) that Leutze had modelled the architectural stage for the battle from a volume of lithographs, published in 1844 by Frederick Catherwood, which contained detailed renderings of ruined MAYAN temples, which Catherwood and archaeologist John Lloyd Stephens had explored in the Yucatan several years earlier. "Leutze copied the giant serpent head in the right foreground, the heads inserted over the doorway and at the base of the tower, and the decorative designs bordering the terraces of the great pyramid. The entire architectural stage appears to be freely adapted from a number of Mayan temples, not one of which closely matches the altarlike appearance of Leutze's structure." (WEST AS AMERICA, p. 59) Never mind that the Mayan and Aztec cultures were far apart in time and space: Leutze senses both as pagan and barbaric.

Older readers and/or science fiction aficionados might also notice the similarity of Leutze's composition, in its flat bas- relief lack of depth, its lurid subject matter, and the clash of alien technology against unprotected beings, to the covers of the old ASTOUNDING SCIENCE FICTION in the cold war inspired decades of the 1940s and 50s. In fact that magazine once published a paraphrase of Prescott's CONQUEST OF PERU as a science fiction story under the title of "Despoilers of the Golden Empire." A further sub-text of Prescott's history also is at play in Leutze's imaging of a turning point in the Conquest--for this painting portrays the moment where, as Prescott conceives it, Christianity overcame Aztec paganism atop the city on a battlefield that was the religious heart of the Mexica.. Part of the US victory of the Mexican War had entailed a perceived victory of an industrious, disciplined, and on the whole, Protestant nation against a backward, indolent, southern, and Catholic nation. In the polarized images of Protestant versus Catholic that occupied the imagination of mid 19th century America, "southerness", laziness, and strange, even quasi-pagan rituals were associated with Catholicism: industry, vigor, discipline, and clean productive harshness accrued to images of Protestantism. Thus, somewhat strangely, the values of Prescott's narrative of the conquest tend to assign to the conquering Spaniards and Cortez the to-be commended qualities of Protestant virtue, zeal, and technological innovation--even though in historical fact the Spaniards were, of course, of the Catholic faith. But who becomes the "Catholics" in protestant, Bostonian Prescott's narrative? The Aztec's--in their decadence and strangeness of ritual and through the horrors of their cannibalistic rites as infamously expatiated upon by Prescott, perhaps sensed as paralleling the savageries of the Inquisition, (whose auto-da-fe's in Spain had featured mass burnings of victims in cages). To support this statement it is profitable to consider the language of one of Prescott's concluding paragraphs: phrases depicting the religion of the Mexica are similar to those encountered in writings opponents to Catholicism alarmed by the challenge of Rome. Indeed the Aztecs and "the Romans" are directly linked.

"The influence of the Aztecs introduced their gloomy superstitions into lands before unacquainted with it, or where at least it was not established in any great strength. The example of the capital was contagious. As the latter increased in opulence, the religious celebrations were conducted with still more terrible magnificence; in the same manner as the gladiatorial shows of the Romans increased in pomp with the increasing splendour of the capital. Men became familiar with scenes of horror and the most loathsome abominations. Women and children--the whole nation--became familiar with and assisted at them. The heart was hardened, the manners were made ferocious, the feeble light of civilization, transmitted from a milder race [Prescott refers here to the allegedly benign influence of the Toltecs who had earlier inhabited the valley of Mexico], was growing fainter and fainter, as thousands and thousands of miserable victims, throughout the empire, were yearly fattened in its cages, sacrificed on its altars, and served at its banquets! The whole land was converted into vast human shambles! The empire of the Aztecs did not fall before its time."

(references, William H. Prescott, HISTORY OF THE CONQUEST OF MEXICO, 2 vols., Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1892, II, 351. and Franchot, Jenny, ROADS TO ROME: THE ANTEBELLUM PROTESTANT ENCOUNTER WITH CATHOLICISM, Berkeley : University of California Press, c1994.